YOL – The Full Version was screened in Australia at Cinema Reborn 2019.

Jane Mills is an Associate Professor at UNSW. With a production background in journalism, television and documentary film, she has written and broadcast widely on screen literacy, cinema, censorship, feminism and human rights. Current teaching and research includes: national, First Nation and transnational cinemas, cosmopolitanism, and cinematic borders. Jane is Series Editor of Australian Screen Classics and a member of the Sydney Film Festival Film Advisory Panel. Her films include: Yılmaz Güney: His Life, His Films (CH4) and Rape: That’s Entertainment? (BBC). Her books include: The Money Shot: Cinema, Sin and Censorship, Jedda, and Loving and Hating Hollywood: Reframing Global and Local Cinema. She is currently writing on Sojourner Cinema: An Outsider’s Eye.

Jane Mills comprehensive Program Notes

Cinema Reborn, Sunday 31 March 2019

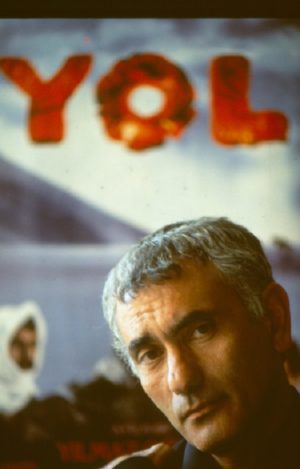

Güney 1982 in Cannes

Yılmaz Güney

Yılmaz Güney’s life (1937-1984) had all the elements of an over-the-top, action-adventure movie with a lot of politics thrown in for good measure. Despite spending a total of twelve years in prison, two in military service, two in enforced internal exile and three years of self-imposed exile in Switzerland and France, he had a prolific film career, acting in 111 films – mainly popular genre movies – and writing/directing twenty films in all, including four that he made from jail by proxy. Filmmaking from jail by proxy? Yes, Güney’s contribution to cinema is unique.

film art to oppose political oppression

When recounting Güney’s life it’s not easy to separate fact from fiction: megastar, poet, novelist, internationally renowned award-winning film director, militant propagandist, revolutionary democrat, dangerous communist, chardonnay socialist, political prisoner, murderer, exile, traitor – Güney was, or was accused of, all these. When I met him just four weeks before he died to film an interview for the documentary I was making, of one thing I was absolutely certain: Güney was committed to using his film art to oppose political oppression and to further democratic freedoms.

Clint Eastwood, James Dean, and Che Guevara combined

Village Voice critic J. Hoberman grasped the uniqueness of this extraordinary filmmaker when he described him as “something like Clint Eastwood, James Dean, and Che Guevara combined.” The Greek-American director Elia Kazan lauded him for having revolutionized Turkish cinema and bringing a realism to the Turkish screen that few could match. The Greek-French Costa-Gavras, whose film Missing shared the Palme d’Or with Güney’s Yol in 1982, was such an admirer that he introduced this once banned film at its legal Turkish premiere in 1993. For Austrian auteur Michael Haneke, Güney’s films are “the essence of life.” For the Turkish-German, younger generation director Fatih Akin: “Güney was a warrior. His movies are full of passion. He had a passion devoid of any compromise: an extraordinary strength. He’s a master of “realist” cinema. Contemporary Turkish cinema is still inspired by his basic dry realism [and] capacity for saying lots of things using just a few scenes.”

symbol of the oppressed – a folk hero

Opinion from inside Turkey was more divided. Both adored and execrated, views about Güney and his films tends to depend on where the admirer or detractor stands politically. For Onat Kutlar, founder of the Turkish Sinematek and life-long opposer of censorship, Güney was “a symbol of the oppressed – a folk hero, a combination of saintliness and courage.” This clearly was not the opinion of the 1961, 1971 and 1980 military juntas that censored or banned every one of the Güney’s films and imprisoned him on charges including criticising the constitution, spreading communist propaganda, harbouring wanted militants, and killing a judge. For his many millions of Turkish and Kurdish fans, however, Güney was the people’s artist, an adored hero-legend they called simply çirkin kral or the “ugly king.”

Background

Güney was born to a peasant family in the cotton-growing area of Adana Province in south-eastern Turkey to which his mother’s Kurdish family had fled from the Tsarist armies during WW1 and his father, a Zaza Kurd, had found refuge from a family vendetta in central Turkey. In the 1950s, Güney worked for a film distributor to pay for his education and found work with the director Atıf Yılmaz, a significant figure in Turkish cinema, who encouraged his protégé to write and act. After a short stint at Istanbul University studying economics, Güney was imprisoned for spreading communist propaganda in a short story he had previously written while at school. As he explained to me, at the time he literally hadn’t known what or where this thing called “communism” was. But the 1960 military junta, although it would introduce some constitutional democratic rights, was not interested in listening to a young, would-be film actor firebrand.

a star in His country

Throughout the 1960s, Güney’s career as a film star hit stratospheric heights: in 1965, he starred in 21 of the 215 films shot in Turkey that year. As he explained, many were Hollywood remakes: “I played the Marlon Brando role in a re-working of One-Eyed Jacks, the Jack Palance role in an imitation of I Died a Thousand Times, and I starred in several James Bond-type films. I was also in 10 Fearless Men… yet another variation on Seven Samurai, inspired by The Magnificent Seven. The others … were not particularly Turkish… but they were the ones that made me a star in my country.”

Like any visitor to Turkey in the 1960s and 1970s, I recall vividly the impossibility of entering a shop, café, taxi, bus, office, classroom or home without seeing pictures of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and Yılmaz Güney. More often than not, there were more photos of the Çirkin Kral than of the founder of the Republic. Legend – and some legends are too good not to print – has it that at outdoor screenings of films in which an enemy was depicted creeping up behind the Ugly King, audiences would take out their guns and shoot at the enemy, leaving screens all over Turkey shot through with bullet holes.

Güney began directing in the mid-60s, a time of increasing political turbulence culminating in the repressive military coup of 1971 that would reverse previous democratic gains. During this period, he founded his own film company to make films that fused his star appeal with his leftist politics. He was interrupted by two years compulsory military service but in 1970, he wrote, directed and starred in Umut (Hope) that for many is a social realist masterpiece. This film proved to be the turning point both for Güney and for Turkish cinema. Drawing on personal experience and demonstrating compassionate political conviction, Umut makes a powerful and moving statement about the futility of isolated, individual action and the necessity of group solidarity, a conviction that became the uniting thread of his subsequent films. Umut was banned and Güney was sentenced to internal exile. In the next few years, despite spending another two in prison, Güney made several successful films including Ağıt (Elegy, 1971) and Arkadaş (Friend, 1974). In 1974, he was arrested and convicted for killing a judge and sentenced to 18 years in jail.

sentenced to 18 years in jail

Did Güney murder the judge? The many legends don’t all agree, convince or align. Some say he did, others say his nephew used his uncle’s gun, yet more leave the verdict open, not least because the prosecution case lacked the forensic evidence to justify the conviction. But, as Güney told me, he was not prepared to discuss the case as this could only implicate friends.

scripts from prison

For the next seven years, Güney wrote scripts from prison and supervised their filming: he “instructed” rather than physically directed Sürü (The Herd, 1978) and Düşman (Enemy, 1979), both of which were directed on location by Zeki Ökten. A legend here tells of the rushes for these films smuggled into his prison and projected on his cell walls. A slightly different version claims smuggling was unnecessary because Güney’s jailers were big fans who positively welcomed seeing their hero’s rushes.

Following the 1980 military coup, the third in as many decades and each more repressive than the previous, Güney was in prison facing the prospect of a further 25 years for charges relating to his political views and writings. The repressive political environment meant that many fans were too frightened to have his photo in their homes and workplaces or even mention his name publicly for fear of persecution. Realising that from now on, every film he ever made would be banned, Güney reportedly said: “There are only two possibilities: to fight or to give up. I chose to fight.” His last two films, Yol and Duvar (The Wall, 1985) are testimony to this pledge.

Fight till death

This time, many of the legends are undoubtedly true: Güney’s filming notes for Yol were smuggled out to Şerif Gören who had previously filmed Güney’s film Endişe (Anxiety,1974) and who had himself just completed a prison sentence on a spurious political charge. After the shoot, the rushes were smuggled out to Switzerland. In the final part of this careful plan, Güney exploited the prison parole system to flee to Switzerland where he edited Yol. After Yol won the Cannes Palme d’Or, Güney was granted political asylum in France and he moved to Paris where he made his last film, Duvar (The Wall, 1983).

[Remark Donat Keusch: Güney’s script Bayram was very detailed and was full of notes re. the filming. A nice version was submitted to the censorship committee. Yılmaz reduced the ten stories of ten characters to six after a discussion and the signature of the production agreement with Cactus Film. Güney Filmcilik agreed to guarantee the production management for the shooting. Cactus Film provided them with funds, a Ford Transit, 25.000 meters of 35mm Fuji negative, some small generators, spotlights and more. All material was imported with a Carnet A.T.A. to Turkey and exported the same way seven months later. I organized and executed with the help of some friends the escape of Güney and his family from their country. They got asylum in France where Yol was edited in the small town of Divonne on the other side of the border near Geneva. The Güney family moved to Paris in March 1982. There the last editing was executed and at the sound studio Marcadet the dubbing and mixing took place.]

His funeral at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris was attended by thousands of fans, comrades and political supporters. It’s unlikely, however, that anyone living in Turkey at the time would have dared travel to Paris to make their farewell: Turkish secret police and informers were doubtless also among the mourners.

Güney’s films and writings were immediately banned in Turkey until the 1990s when the Turkish premiere of Yol took place. But even at this screening his most celebrated and courageous film was censored: the shots with the word “Kurdistan” had to be removed before the authorities would permit the screening.

YOL (1982)

Yol, a bleak, angry, sprawling film, follows the emotional and physical journeys home of a handful of prisoners granted a week’s leave from the prison island of Imralı in the Sea of Marmara – the very jail where Güney was imprisoned.[1] As they travel by bus and train against the ticking clock (they have to be back within the week or else suffer a further sentence), the men discover that they are no more free outside prison than they were inside. Güney’s Turkey is one large prison in which the people are oppressed by political tyranny, the ever-present military and by superstition, bigotry, religion and patriarchy. The women, especially, are trapped by traditional values and codes of masculine “honor” that reduce them to possessions as the men pursue futile vendettas and revenge killings. Şerif Gören who filmed according to Güney’s detailed instructions brings his own cinematic skills to the film, capturing a people in brutally beautiful landscapes caught between the destructive forces of modernization and feudalism.

All the prisoners experience sadness, despair and oppression on their journey. The oppression often comes from those who are themselves oppressed – by the military regime, feudal traditions, contemporary capitalism, nationalism, and by religious intolerance. Güney’s conviction of the futility of individual action and the need for solidarity and unity in collective action is nowhere more strongly represented than in the storyline of Ömer (Necmettin Çobanoğlu), the Kurdish character with whom many think Güney closely identified. To the soundtrack of a haunting Kurdish song, Ömer leaves his family and his village to head across the border to join his fellow Kurdish rebels in Syria. Like Güney, Ömer finds freedom by choosing to fight rather than submit to military or feudal law.

With its inclusion of Kurdish dialogue, music and song, there was little likelihood Güney would be able to oversee the edit and, even had he been able to do so, no likelihood at all that the film would ever be shown in Turkey. “The Kurdish struggle, as shown in Yol,” Güney said later “is probably the most visible face of the resistance.… If Turkey can achieve a true democracy, then all minorities will have the right to speak up…”

Outside Turkey, Güney’s decision to flee and edit Yol in voluntary exile so that it could be seen by audiences outside a Turkish film was rewarded not only by winning the Palme d’Or but also awards from the International Federation of Critics, the Ecumenical Jury, the French Critics’, the London Film Critics Circle, and the US National Board of Review. In Turkey, however, the military regime sentenced Güney in absentia to an additional 20 years in prison, revoked his citizenship, and confiscated and banned all his films including those he had directed and scripted and those in which he had acted.

THE RESTORATION

“Yol is living proof that it is not a director who makes a film but rather a team. It is a collective work whose spirit reaches from the stormy 1980s right up to the current day with its origin in Yılmaz Güney’s life and the script he created.” Donat Keusch, Producer of Yol – The Full Version (2017)

The restoration for Yol – The Full Version (2017) screening at Cinema Reborn is from the original 35mm negative, the interpositive and positive prints; the new sound mix is from the original digitized tapes. This, however, is only a small part of the restoration story which has created almost as much controversy as did Güney himself for much of his filmmaking life.

For years, Yol existed only as poor quality 35mm film prints and illegal digital copies, all made from the1982 Cannes version. According to Donat Keusch of Cactus Films, the Swiss producer and distributor of Yol (1982), upon seeing Güney’s cut, Cannes Festival Director Gilles Jacob insisted that the film’s length should be not more than 110 minutes or he would not consider it for inclusion in competition. Therefore, 27 minutes were edited out. This shorter version was completed almost overnight with several voices hurriedly dubbed live by Güney, many female voices supplied by a single actress, and no time to fine edit the sound tracks. After it was banned in Turkey, the first official screening didn’t take place until 1993 when the Swiss producer and distributor was forced to remove the shots with the word “Kürdistan” emblazoned on them when Ömer reaches his homelands. Apart from this, nothing else was changed; it was still the hurriedly edited version made for Cannes in 1982.

Two years later another version started to circulate illegally in Turkey in which all voices were changed. This is particularly sad because Güney’s voice can be heard in the Cannes version and in the restored and completed Yol – The Full Version: he dubbed the voices of the tooth puller and the old man at the bus stop who asks for a cigarette. The original voice of Güney is that coming from the prison loudspeakers in the opening and the end sequence. Thirty-five years after Yol won the Palme d’Or, and in the year that Yılmaz Güney would have turned eighty, Yol – The Full Version, was screened at the Classics section of the Cannes Film Festival. Not everyone is happy with this restored version. Impassioned protestors accuse the Swiss producer of censorship, pointing out discrepancies between the length of the versions that screened at Cannes in 1982 and the 2017. They point out that the “full version” has six, not five, prisoners travelling back home on their week’s leave and are concerned that the sixth is not as sympathetic as the other main characters. Of major concern was the continued absence of the word “Kürdistan”. However, what the protestors were not party to, and are presumably unaware of, is the much longer version of Yol that Güney approved before being compelled to make several hasty edits at Gilles Jacob’s insistence. Yol – The Full Version represents all stories Güney scripted in Bayram, the title of his script, and wanted to be in his film before this Cannes Film Director’s insistence and pressure. In fact, he didn’t want this film for his program – the title Yol can’t be found on his final handwritten list of films for competition.

Keusch defends the “Full Version,” explaining that when he asked Elizabeth Waechli, who had edited with Güney back in 1982, to work on the restoration, she produced 469 pages of notes she had made at the time. These notes were the precise instructions for the cut that Güney had initially wanted and he followed them for the 2017 full version. In fact, Güney had originally envisaged a much longer film with eleven prisoners but the exigencies of producing Yol (aka Bayram) by the Swiss company Cactus Film meant that Güney/Gören had to reduce these to six. In the last frantic minutes of editing before submitting the film to Cannes for inclusion in competition, the unpleasant character – a member of the Adana gambling mafia who cheats on his wife and visits prostitutes – was cut out. He is restored in Yol – The Full Version according to Güney’s original script and to his editing plan of February 1982. The same was done with the second half of Yusuf’s story which is finally comprehensible in Yol – The Full Version.

More than this, for years Keusch had assumed that the poor picture quality was the work of cinematographer, Erdoğan Engin. But a test-scan of the original negative in 2012 showed that Engin’s camerawork was very good despite the difficult weather conditions and circumstances in which he’d had to film. The poor copies were actually the result of unsatisfactory laboratory work. Digital restoration technology has meant that the picture quality as well as the sound track is now much improved. And at last, the wonderfully evocative music by Zülfü Livaneli can now be properly acknowledged: in the 1982 version he was credited under false names (Sebastian Argol, Kendall) to protect him from possible persecution. Controversially, to enable it to be presented by the official Turkish stand at Cannes in 2017, the two shots showing the word “Kürdistan” were removed. However, the real complete version exists for the international market with all the politically controversial inserts included.

________

[1] Imralı is where Abdullah Öcalan, leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) has been incarcerated since 1999, much of the time in isolation. It is also the prison from which Bill Hughes, the American author of Midnight Express, escaped.

________

Copyright: This Program Note is in copyright and subject to the protections of the Copyright Act 1968. Please see additional information at https://library.unsw.edu.au/copyright/for-researchers-and-creators/unsworks

Permissions: This work can be used in accordance with the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license.

Please see additional information at https://library.unsw.edu.au/copyright/for-researchers-and-creators/unsworks