Şerif Goren, Yılmaz Güney (by proxy)

Transcripts of the introduction at Cinema Reborn 2019 which took place at The Ritz Cinema in Randwick from 2-6 May.

Acknowledgment of country: the Bidjigal people. It is particularly appropriate to acknowledge Australia’s indigenous people because it connects to the film we’re about to see that acknowledges Turkey’s indigenous Kurdish people.

I first saw Yol in 1982, in London’s Lumière Cinema (now a fitness gym), tucked behind Trafalgar Square in St Martin’s Lane. From the moustaches and headscarves of the most of the audience, I assumed most of the audience was Turkish. But not so. At one point in the film, the audience suddenly erupted – literally exploded – into cheers, claps, shouts and tears. It was the point when the word “Kürdistan” appeared on the screen. Their joy made me realize that the audience was, of course, Kurdish. This was the first time they had ever seen a film openly depicting their own people, language, and homeland. It remains the single most moving cinematic experience I’ve ever had. And at that moment, I knew my next film had to be about Yılmaz Güney. [1]

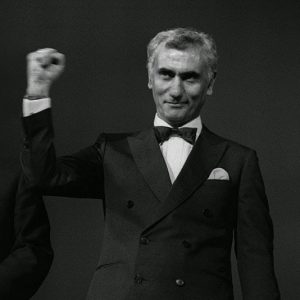

Yılmaz Güney

Güney was described by the critic J. Hoberman as “something like a combination of Clint Eastwood, James Dean, and Che Guevara.” [2] A big claim but, if anything, a gross understatement. Güney was a hugely popular film star of action, adventure and western knockoffs before he became Turkey’s politically committed cinematic voice of protest.

Güney was many things: megastar, poet, novelist, award-winning director, Marxist, militant propagandist, revolutionary democrat, dangerous communist, chardonnay socialist, political prisoner, bandit, saint, exile, traitor – and murderer: Güney was, or was accused of, all these.

Despite spending a total of twelve years in prison, two in military service, two in enforced internal exile and three years of self-imposed exile in France, he had a prolific film career. He acted in 111 films, wrote and directed twenty films – three of which he made from jail – by proxy. Filmmaking from jail by proxy? In 1974 Yılmaz was convicted of murdering a judge and sentenced to 19 years imprisonment. But prison didn’t stop him from making films. As a filmmaker, he was undoubtedly unique.

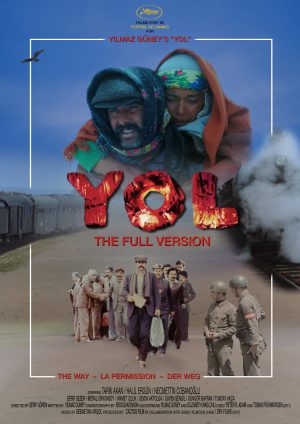

Yol– The Full Version

Şerif Goren and Yılmaz Güney (by proxy), 2017

First, a little about the film we’re about to see. It follows 6 prisoners who have been granted a week’s parole to travel back to their homes. All the prisoners experience sadness, despair and oppression on their journey. The oppression often comes from those who are themselves oppressed by the military regime, feudal traditions, contemporary capitalism, nationalism, and by religious intolerance.

Yol presents Turkey as one large prison in which the people are oppressed by political tyranny, the ever-present military and by superstition, bigotry, religion and patriarchy. The women, especially, are trapped by traditional values and codes of masculine ‘honor’ that reduce them to possessions as the men pursue futile vendettas and revenge killings.

Güney’s conviction of the futility of individual action and the need for solidarity and unity in collective action is nowhere more strongly represented than in the story-line of Ömer (Necmettin Çobanoğlu). He is one of three Kurdish characters with whom many think Güney closely identified. To the soundtrack of a haunting Kurdish song, Ömer leaves his family and his village to head across the border to join his fellow Kurds where he will fight for Kurdish liberation. Like Güney, Ömer finds freedom by choosing to fight rather than submit to military or feudal law.

Şerif Gören who filmed on location according to the detailed instruction Güney gave him in prison brings his own cinematic skills to the film. [3] He captures a people in brutally beautiful landscapes caught between the destructive forces of modernization and feudalism.

Meeting Yılmaz Güney

For my film, I interviewed Yılmaz in Paris in 1984. I’d heard he was ill but I was unprepared for the desperately sick man I met. My interview took all day because every 45 minutes or so he would have to lie down to gather his strength. But he insisted on going on to the end of my many questions. 3 weeks later, Yılmaz died of cancer.

What follows are some of my questions and Güney’s answers at this interview.

1. How did you make film from prison?

I must say this is not true. In prison, I only created the conditions for making it. The success of all my films is the success of my friends who worked on them. These friends acknowledge my part in this success, as I acknowledge theirs.

2. How did censorship affect you?

Every one of my films has been censored or banned. To make films about the reality of Turkish life, I had to take precautions against this monster. So, I based my message on a particular language that was formed between me and the people. I developed a sort of Aesopian language. [4] It enabled me to speak to the masses.

This raises the fascinating issue of whether censorship can be productive and contribute to the creative process.

3. Why do you stress Kurdish oppression in Yol?

There are 12 million Kurds in Turkey without democratic rights. Can you conceive of a people who can’t sing their songs in their own language? Who are denied the right to say “we exist; we are Kurdish”? In Yol, I was able to bring this issue to millions of people who were unaware of it. This was my democratic duty.

4. Under prison conditions, how did you write the script and instruct Şerif Gören to direct Yol on location?

There is no need for modesty. I am Yılmaz Güney. When I plant my feet on Turkish soil, I achieve a lot. I organized every prison I went to. I organized the prisoners as well as the guards. I prepared the most detailed plans to achieve my films. I can’t go into how I did this, as it would bring trouble to those who were involved.

5. Why did you flee from prison and from Turkey?

Yol came into being as a means of struggle. It was getting impossible for me to make films from prison. The longer I was inside, my relationship with the Turkish people got weaker. Oppression – torture, censorship – was increasing. On top of this, I was being tried for more crimes – for my writings. To remain in prison under these conditions meant giving up. I could no longer stay in Turkey. There were only two possibilities: to fight or to give up. I chose to fight.

Things to look out for while watching this film

- Güney’s voice can be heard several times – he dubbed the voice of the dentist, the man in bus depot who asks for a cigarette and the prison loud speakers.

- Shots of İmralı prison – this is where Yılmaz was himself imprisoned.

- The scene in the toilet on a train – this is an example of Güney’s ‘Aesopian language.’ Politicized Turks in the audience would know that this scene is said to have actually happened to the famous Communist poet, Nazim Hikmet, when he met his wife while on parole from prison. But that time, in an era before the military juntas dehumanized the Turkish people, the other passengers on the train helped the dissident and his wife find a space to be together.

Conclusion

Tonight’s film is not quite the film that won first prize at Cannes. This restored “full version” is the cut that Yılmaz signed off on before he was required to make some quite cuts to satisfy the conditions stipulated by the Cannes Festival. However, thanks to the persistence of the Swiss producer, Donat Keusch, the detailed notes of the Swiss editor Elizabeth Waelchli [5] and to digital restoration technology, it is the film that Güney wanted us to see.

Jane Mills

UNSW. May 2019

_______________

[1] Yılmaz Güney: His Life, His Films (Jane Mills, 1987) made for Try Again Ltd and transmitted on Channel 4 in 1987 to introduce a short season of Yılmaz Güney’s films. Narrated by Julie Christie; Güney’s voice by Mark Shivas

[2] J. Hoberman, “Listen, Turkey”, Village Voice, November 23, 1982

[3] Gören co-directed Umut/Hope (1970) with Güney and completed filming Endişe/Anxiety (1974) after Güney was arrested for murdering Sefa Mutlu, the public prosecutor of Yumurtalık district in Adana Province in a drunken argument.

[4] Aesopian language: a term coined by Russian satirist Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin in Letters to Auntie (1881-1882), to designate a “figurative language of slavery”, an “ability to speak between the lines… at a time when literature was in a state of bondage.” The practice of this elusive discourse is investigated in Lev Loseff’s study, in which he defines Aesopian language as: “a special literary system, one whose structure allows interaction between the author and reader at the same time that it conceals inadmissible content from the censor.” (On the Beneficence of Censorship: Aesopian Language in Modern Russian Literature, Munich: Otto Sagner, 1984)

[5] Elizabeth Waelchli was co-editor (with Güney) in 1982