Reasons for the Restoration

Costa-Gavras – Yılmaz Güney – Vittorio Gassmann Cannes 1982 award ceremony

Due to the continued and increasing interest in Yılmaz Güney‘s YOL, I finally started restoring our most successful film in 2012, 30 years after it’s inception. YOL (The Way) won the Golden Palm together with Costa Gavras’ MISSING in Cannes. The two exiles, the one Greek, the other Turk-Kurd met for the first time at the award ceremony on the stage of the old Festival palace and became friends.

YOL was presented at the Cannes Film Fest in a less than beautiful, unfinished form. This was because the festival director at the time, Gilles Jacob, did not want the film.Under pressure from the minister for Culture, Jack Lang, he capitulated at the last second and allowed YOL to participate in the competition. For ostensible programming reasons, he demanded however that Yılmaz Güney‘s YOL not exceed 110 minutes in running time. He was probably guessing we wouldn’t manage it for lack of time.

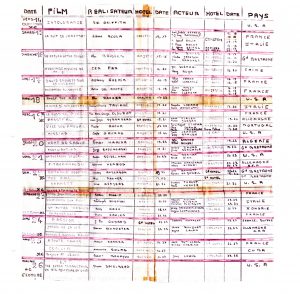

Gilles Jacob’s definitive handwritten program structure of competition films in Cannes 1982 – without mentioning YOL

In order to give the creator of YOL, filmmaker Yılmaz Güney, who had in the autumn of 1981 become a Turkish exile, to make a start in Europe we had to be in the competition at Cannes.

We wanted to finally finish the film after the festival, but unexpectedly winning the Golden Palm changed everything. We distributed this unfinished and shortened version of YOL worldwide. At that time the Golden Palm was still a seal of quality. But this version of YOL did not correspond with Güney’s script BAYRAM, nor with his and the cutter Elizabeth Waelchli’s editing plan.

With the help of the editors Tobias Frühmorgen and Peter Adam (“Good-Bye, Lenin!”, the director’s cut of Schlöndorff’s “Tin Drum” and many more) I succeeded in reassembling YOL in such a way that it fulfils Güney’s original specifications. We have packed around 7% more content whilst maintaining almost the same running time of 110 minutes. As in Güney’s script and editing plan, we tell the full story of Süleyman, the sixth prisoner on leave. This also applies to the young Yusuf, whose problem is finally understandable in “YOL – The Full Version”. Essentially, the never-finished montage of the film had to be finally completed. Unclean transitions between settings and scenes had to be smoothed out and unnecessarily long scenes trimmed. These loose ends came about as a result of time pressure in 1982, at the hands of the director of the Cannes film festival and his unbelievable demands.

The montage work was completed over a few months with YOL-material from DVD’s. The discarded material from 1981 (6 hours worth) was stored on VHS-tapes and was copied to DVDs. – After completion of the montage, the original negatives, as well as the re-inserted take-outs from the leftover negatives and some working print material, were digitized and restored in 2K. The majority of the sound had to be redone. This was also true of the reinserted sections, as the film was shot without sound.

In 1982 “YOL” was not released in some regions for political reasons. One couldn’t watch the film on Turkish television either. The interest in a completed YOL is high, certainly in relation with the growing importance of Turkey and the Kurdish question which remains since more than 100 years unsolved. YOL portrays the mentality and living conditions of Turks and Kurds better than any other film. Much like Yılmaz Güney’s script, exposé and his original editing plan, YOL – The Full Version is better, more exciting and more presentable than the unfinished 1982 Cannes cut down version. YOL was awarded the Golden Palm from the jury for political reasons.

The tablet of city names and the insert of KURDISTAN in the film YOL

At the first screening of YOL’s rough cut in Paris, put on for a German investor, the audience struggled to get themselves along in the film geographically. After much deliberation, Yılmaz was persuaded to mix in the destinations of each of the six prisoners. And we wanted to know where Kurdistan is in the film. Yılmaz was astonished because for him it was clear from the clothes and the attitude. Finally, he concurred and placed the insert “Kürdistan” in the blue sky. He insisted on the “Ü” in the word. The word Kürdistan prevented the distribution of YOL in Turkey, but we weren’t concerned. Because after Yılmaz’ getaway, his films and YOL especially were banned in Turkey.

When the first official performance of YOL was allowed in Turkey in 1993, Fatoş Pütün(-Güney) demanded that this insert has to be cut out. I had brought a new 35mm film print to Istanbul and was against censorship. But Fatoş insisted. It would have been impossible to show the film in the big sports stadiums otherwise. So I cut this little piece out and took it with me. Sadly I trusted Fatoş Pütün and left the 35mm film print there. She later produced a 35mm negative of it and distributed the film illegally throughout Turkey, obviously without the insert Kürdistan. Since at least the May 27, 2003 court ruling she has no rights to the film as producer or distributor. She forgot that with my escape plan and my personal commitment Yılmaz, she and the two children were able to escape from prison and from Turkey.

Yılmaz Güney didn't film in Kurdish

Güney made the film for his Turkish and Kurdish and all the other compatriots of Turkey. Their living conditions, their morals, their traditions, unadorned and critically presented. Nobody could do that better than him because he loved the people and wanted to help them. He wanted that his films should be seen in cinema theaters. The greatest Turkish-Kurdish film of all time, in my opinion, SÜRÜ (The Herd), which tells the story of a Kurdish rural clan, was also shot in Turkish. The film could thereby pass the censorship requirements and could be shown in Turkey, its message understood by all. Yılmaz Güney’s films have to be screened in cinema theaters, not on mobile phones and other smaller screens. The most important thing for the greatest Turkish-Kurdish filmmaker was that his films be shown in his homeland.

Yılmaz Güney had to leave his country

By the time of my first meeting with him in summer 1979 Yılmaz was convinced that he would be let out of prison on the expected amnesty at the end of next year. But in September 1980 there was a military coup and a fascist government was established under general Evren. There were instituted new legal proceedings against Yılmaz Güney because he had mentioned Kurdish culture and the oppression of Kurds in welcome messages addressed to European film festivals where we screened his films. He then understood he’d never be released. Therefore, he had to decide escaping from the prison and his country. At his request I drew up an escape plan for him and his family. Under my leadership, a French captain, a German scout, Yılmaz’ Turkish confidant and some auxiliaries helped him to leave his country during the Bayram holiday period on October 1981. I convinced an international film festival to invite his wife as a jury member but accompanied by Yılmaz’ two children. The whole operation was very difficult. First because everyone in Turkey knew who Yılmaz was and second as Turkey was embroiled in a conflict with Greece and on the point of war. The border coast at the Aegean Sea was packed with soldiers. We were happy to leave the little bay south of Kemer (Gulf of Antalya) in our rented yacht. Yılmaz, on the other hand, was sad that he had to leave his homeland. – I won the first game of chess against Yılmaz after the storm on the Mediterranean was over – a feat I never managed to repeat afterwards.